Brain disorders caused by large effect mutations in single genes often present unexplained large symptom diversity, even among carriers of the same mutation. In the new study, a collaboration between FGA and the university of Copenhagen, the authors examined genetic interactions as a possible explanation for this diversity for SNAREopathies, a group of common neurodevelopmental disorders caused by de novo genetic variation in genes that together drive secretion of chemical signals in the brain. SNAREopathies are characterized by a striking phenotypic diversity, including different types/degrees or absence of seizures, developmental delay and intellectual disability.

The authors tested the hypothesis that large phenotypic diversity is caused by non-linear genetic interactions between two or more functionally related genes by combining validated SNAREopathy mouse models and comparing phenotypic diversity between single and double mutants at the synaptic, network, system and behavioral level. Single Stxbp1 and Snap25 mutant animals showed EEG- and motor abnormalities, but no seizures, as reported before. In contrast, double mutants exhibited extreme diversity in seizure phenotypes. Some mice had lethal generalized seizures, frequent and complex epileptiform EEG activity and thalamic hyper-excitability as indicated by increased cFos staining, while other mice of the same genotype showed no detectable abnormalities, no increased cFos staining and a normal life span. The surviving double mutant mice showed phenotypes not more severe than single mutants at the synaptic, network, and behavioral level.

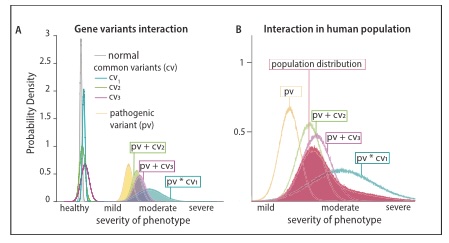

The authors also present a theoretical framework to quantitatively explain the observed non-linear effects and extrapolate the conclusions to symptoms diversity in human patients. This study provides a proof of concept for how modifying genes in the patient genome enhance phenotypic diversity.

The study can be found here.

Representing the Molecular Neurodegeneration group, she built on previous findings from the lab showing that astrocytes display stress responses to intraneuronal tau pathology. Using human cellular models, she identified a mechanistic link between increased oxidative stress and the activation of the integrated stress response. She further investigated the physiological consequences for astrocytes.

These results provide new insights into how astrocytes respond and adapt to intraneuronal tau pathology, which could potentially elucidate targets for therapeutic intervention.

Thijmen Ligthart from the Molecular Neurodegeneration lab has been awarded the presenter prize at the annual meeting of the Dutch Protein Aggregation Network (DPAN), a national platform that brings together researchers studying protein misfolding and aggregation.

In his presentation, Thijmen described recent findings from the lab demonstrating that granulovacuolar degeneration bodies (GVBs) identify a neuronal state that is resilient to tau-induced impairment of protein synthesis. Using cellular models of tau pathology, this work reveals that GVB formation is associated with the preservation of translational capacity, leading to increased survival under proteostatic stress.

These results provide new insight into how neurons adapt to tau-induced neurodegeneration and suggest that GVBs may serve as a marker of cellular coping mechanisms in tauopathies.

Neuroscientsts Angela Getz and Maxime Malivert (FGA/CNCR), and their colleagues in France, Canada and the U.K. discovered the new insights, as published in Neuron. These results open up new avenues of research.

Using new molecular tagging and advanced imaging approaches, the researchers visualised the molecules that transmit signals at the receiving side of the synapse. This approach allowed them to track these receptors in real time in intact brain tissue and follow their movements across the surface of synapses. The same approach also allowed them to manipulate the mobility of these molecules and ask how their mobility contributes to information processing.

Synapses have their own built-in gain control

The researchers observed that this mobility plays a crucial role when synapses are activated at high frequencies. Under normal conditions, the receptors temporarily desensitise after repeated activation. Their mobility allows new receptors to move into the synapse and replace those that have become desensitised, thus maintaining strong signal transmission. When their mobility is blocked, desensitised receptors remain trapped in the synapse and transmission decreased sharply, acting as a brake.

This mechanism therefore acts as a gain control; an acceleration or deceleration system integrated into each synapse. Remarkably, not all synapses rely on this principle in the same way. Depending on their architecture and molecular properties, some are very sensitive to receptor mobility, while others are much less so. Each synapse thus possesses its own “dynamic signature” of information processing.

Receptor mobility opens new paths for brain research

The researchers also show that when the brain stores new information, it does so by modifying this receptor mobility. These results open up new avenues of research: many physiological or pathological factors – stress, aging, neurodegenerative diseases – may be influenced by modulating receptor mobility.

Assistant professor Angela Getz, post doc Maxime Malivert and their team have established these advanced imaging setups and techniques in the VU Research Building. They currently investigate how architecture and molecular properties of different synapses determines their “dynamic signature”. They also train master students to operate the set up and visualize individual molecules in intact brain tissue in real time.

The human brain has unique cognitive abilities compared to animals. However, it is also vulnerable to diseases that bring cognitive decline and neurodegeneration, such as Alzheimer’s. What makes the human brain so different? Neuroscientist Goriounova’s team thinks the answer lies in the function of neurons in our brains. Over the course of evolution, our neurons could have developed properties to process information faster and more efficiently in a larger brain, but which also made the neurons more vulnerable.

Neurons

Previously, Goriounova showed that the human brain holds specialized neuron types with distinct properties associated with IQ scores. These neurons could be crucial to human cognition because they are selectively lost in cognitive impairment. How these neurons function and form connections in the human brain is still unknown.

In her ERC proposal, Goriounova will test her prediction that cortical computation in the human brain depends on a highly interconnected network of these special types of neurons, which form fast and strong connections and can be fine-tuned by specific receptors to increase computational power.

Live brain tissue studies

These questions can only be investigated in adult living human neurons in their intact networks. This is extremely challenging because of the difficult access to human brain cells. Goriounova therefore collaborates with several hospitals in the Netherlands treating people with tumors or epilepsy. During surgical treatment, the neurosurgeon also removes a small piece of healthy cortical tissue to access the focus of the disease. This human brain tissue can be kept alive and used to study how neuronal cells function in their intact connections.

By collecting preoperative data from the same patients, the team can now link neuronal function to live brain network activity and cognitive scores of these patients. These methods make it possible to answer the question of the specialized function of human neurons relevant to cognition.

Consolidator Grant

The ERC uses the Consolidator Grant to support outstanding principal investigators for a period of five years at the career stage when they may still be setting up their own independent research team or program. Goriounova will receive €2 million for her project.

Alzheimer Nederland awarded €121,650 to Dr. Douglas Wightman (Complex Trait Genetics) to investigate genetic and environmental prediction of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease presents later in life but the biological processes that contribute to the disease development start well before symptom onset. Early prediction of Alzheimer’s disease risk before symptom onset would be beneficial in directing individuals to care earlier and may allow for more effective treatment.

In this project, Douglas will use machine learning methods to combine genetic risk and environmental risk to better predict Alzheimer’s disease. Models of genetic risk will be based on recent large genome wide association studies. There is a specific aim to create a minimal model that limits the number of features for easy clinical implementation.

This research aims to priortise genetic and environmental factors that can accurately

New research published in Cerebral Cortex https://academic.oup.com/cercor/article/35/8/bhaf127/8233140 reveals that many of the genetic changes that shaped the human brain and cognition, and even our vulnerability to mental illness, are surprisingly recent in evolutionary history.

The study, led by Ilan Libedinsky and Martijn van den Heuvel from the Complex Trait Genetics lab at CNCR, combined genomic dating methods with data from over 2,500 genome-wide association studies. This approach enabled the researchers to reconstruct evolutionary timelines for traits that cannot be studied through paleontological records, such as brain structure, cognition, and behavior, providing a genetic window into how humans have evolved over the past five million years.

Genes with these recent evolutionary modifications were linked to cortical structure, neuronal development, and intelligence. The same “young” genes were also highly expressed in brain regions involved in language, suggesting that evolutionary recent genetic modifications helped refine the neural circuits underlying complex cognition and communication, hallmarks of the human species. Some of these recent genetic changes were also associated with psychiatric disorders such as depression and schizophrenia.

By tracing when and where genetic variants emerged, the study opens new opportunities to investigate how evolutionary pressures on human-specific traits have shaped the molecular mechanisms underlying brain function and vulnerability.

The Scheper lab will follow-up on their previous work that established that GVB+ neurons are resilient to the tau-induced protein synthesis collapse and neurodegeneration, for which they identified key mechanistic components. Importantly, GVB+ neurons also retain the capacity to acutely induce the synthesis of plasticity factors in response to neuronal activity, showing the relevance of GVB-related resilience for neuronal function.

Supported by this Hersenstichting grant they aim to exploit the intrinsic resilience pathways that are activated in GVB+ neurons towards a therapy for tauopathies.

This 850.000 euro grant will allow him to expand his research team and gain fundamental new insights into the mechanisms and role of mRNA localization and local protein during the formation of synapses.

Each neuron in our brain forms thousands of synapses with other neurons that allows neuron communication. Each of these synapses requires hundreds of proteins that allow neurons to communicate with each other. While we now know which proteins are present in these synapses, it remains a great mystery how each neuron manages to bring these hundreds of proteins together in the right place and at the right time to form all these synapses. It is essential that we understand this because we know it goes wrong in neurological diseases.

In this project, his group will use innovative molecular techniques and live-cell and super-resolution imaging to study the role and mechanisms of mRNA localization and protein production in building new synapses at the right time and place. In addition, they will develop a new method to control these processes in neurons which would allow them to guide synapse formation.

New positions for a PhD student and postdoc will become available next year. For this, keep an eye on the team’s website: https://cncr.nl/research-team/neuronal_mrna_trafficking_and_local_translation/

More information on this VIDI project can be found at: https://vu.nl/en/news/2025/vidi-for-max-koppers-the-role-of-local-protein-production-in-synapse-formation

This community-driven data commons – built in collaboration with a broad network of (international) collaborators – integrates lipidomics from human and mouse brain tissue as well as induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neurons, astrocytes, and microglia.

Using this resource, the authors show that iPSC-derived brain cell types display distinct lipid “fingerprints” that closely mirror those found in living tissue. One striking discovery is that the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk gene ApoE4 promotes cholesterol ester buildup specifically in astrocytes, a finding that aligns with lipid changes seen in human Alzheimer’s brain samples. Further analysis revealed that altered cholesterol metabolism in astrocytes directly affects immune-related pathways, including the immunoproteasome and antigen presentation systems. Strikingly these immune pathways were downregulated in the cholesterol ester accumulating ApoE4 astrocytes, challenging the view that the AD risk mutation ApoE4 increases glial reactivity and suggesting that immune responses may help protect against AD development.

By making these data openly accessible, the Neurolipid Atlas offers researchers an unprecedented platform to explore lipid dysregulation in brain disorders and accelerate discoveries into the molecular underpinnings of neurodegeneration.

The study is now published in Nature Metabolism and can be found here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s42255-025-01365-z